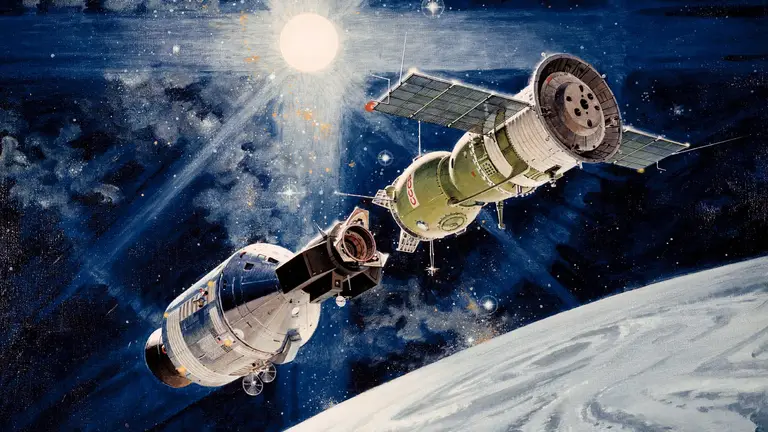

The Apollo-Soyuz mission began with an ambitious agreement signed between the USSR and the USA on May 24, 1972. This was a period when the space race was in full swing, and each country sought to prove its superiority. However, instead of competition, the leaders decided to join forces. The main task was to overcome technical barriers: the Soyuz and Apollo ships were so different that docking them seemed almost impossible.

Two spacecraft, created in different parts of the world, meet in orbit. Their crews, speaking different languages, shake hands through an open hatch. The mission, known as ASTP (Apollo-Soyuz Test Project), became a symbol of scientific cooperation.

The Soviet Soyuz spacecraft was compact, designed for two cosmonauts, with a simple but reliable design. The American Apollo, on the other hand, was a complex vehicle created for flights to the Moon, with three astronauts on board. Even the docking systems differed: the Soyuz had a "probe-and-drogue" mechanism, while the Apollo had a more complex docking module. In addition, the atmosphere inside the ships differed: the Soyuz used air with pressure close to Earth's, while the Apollo used pure oxygen at low pressure. To make docking possible, engineers developed a special transfer module - an "androgynous" docking unit, which became the prototype of modern ISS systems.

Preparation took almost five years. Soviet and American engineers jointly solved technical problems, and cosmonauts and astronauts learned to understand each other, studying languages and culture.

We didn't just get to know each other well. We became close as human beings.

Historical moment

On July 15, 1975, Soyuz-19 was launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome with a crew: commander Alexei Leonov, the first person to walk in space, and flight engineer Valery Kubasov. Seven and a half hours later, Apollo took off from Cape Canaveral with astronauts Thomas Stafford, Vance Brand, and Donald Slayton. Two days later, on July 17 at 19:09 Moscow time, the ships docked in orbit. Millions of people around the world watched this live.

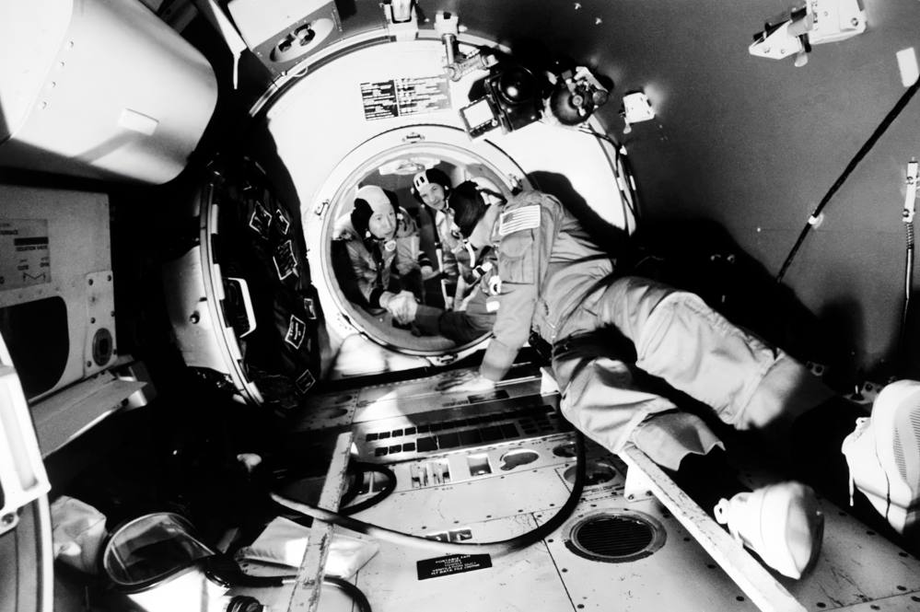

Thomas Stafford was the first to move to Soyuz.

I open the hatch and see Thomas's smiling face in front of me. We had been working towards this for three years. I took his hand and pulled him into my ship.

This moment, called the "handshake in space," became a symbol of unity. The crews exchanged flags, signed a joint document, and even had a friendly dinner.

Russian hospitality is well known, but I didn't expect my comrades to take full advantage of it.

Science in Orbit

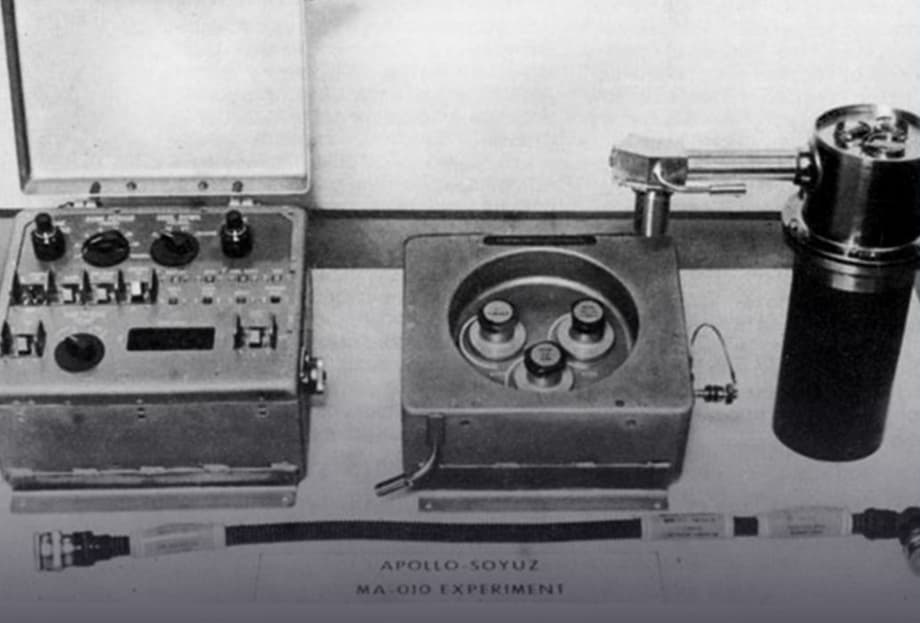

The Apollo-Soyuz mission was not only a symbolic gesture, but also an important scientific project. During 46 hours of joint flight, the crews conducted a series of experiments. One of the most unusual was the VOAL experiment or the "Space Furnace" - an attempt to create an alloy of tungsten and aluminum in space. The name "VOAL" comes from the abbreviation of these two metals, and the very idea of the experiment seemed almost fantastic. On Earth, it is extremely difficult to create such an alloy: tungsten melts at a record 3422°C, and aluminum by this time has long turned into a gas (its boiling point is 2518°C). Under normal conditions, it is only possible to sinter metals, creating a thin layer of one on top of the other.

But in zero gravity, everything changed. A special furnace operated on board the Soyuz, heating the materials to 1000°C. Under microgravity conditions, it was possible to obtain fundamentally new materials - intermetallics with a unique crystalline structure. These alloys combined the strength of tungsten and the lightness of aluminum, opening up prospects for creating ultra-light and heat-resistant structures. Although the industrial production of such materials in space has not yet been established, the VOAL experiment proved that an orbital laboratory can provide what is impossible on Earth.

Our flight is of great importance not only for easing international tensions, but also for the safety of space flights, for science. We conducted several very interesting experiments in this flight, but I would like to highlight the "universal furnace." The samples that we brought from space are being studied in institutes. Final conclusions can be drawn a little later, but it is already clear that space metallurgy was born after our flight. It is possible to create new, unusual materials in orbit that are needed by various industries, primarily the electronic one. Moreover, their production in space is much more efficient than in terrestrial conditions. Now I can safely predict a rapid rise in extraterrestrial metallurgical technology.

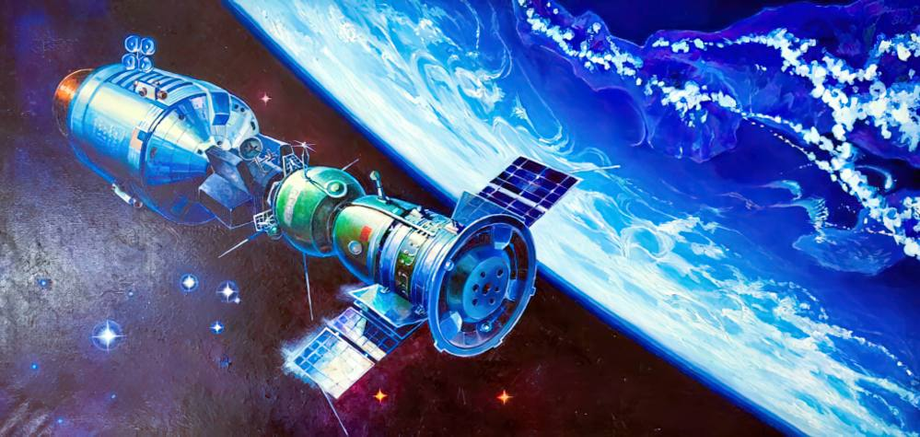

On July 19, the ships undocked, performed a re-docking for additional tests, and finally separated. Soyuz-19 landed on July 21 in Kazakhstan, and Apollo splashed down in the Pacific Ocean on July 25.

I thought that by opening the hatches in space, we were opening a new era in the history of mankind.

This mission laid the foundation for international cooperation in space, which later materialized in the creation of the International Space Station (ISS).

Alexei Leonov, whose artistic talents complemented his experience as a cosmonaut, created portraits of American colleagues in orbit and later wrote the book "Solar Wind," where he described the mission in detail.

Not once has any of the participants in the Apollo-Soyuz program said a single unkind word about the other side.

The Apollo-Soyuz mission showed that science and the pursuit of knowledge can unite people. It became an example of how working together towards a common goal can overcome barriers. Today, when international crews work on the ISS, and plans for flights to Mars are becoming a reality, the "handshake in space" remains an inspiring symbol.

Space does not belong to one country. It belongs to everyone who is ready to explore it together.

Almost 50 years have passed since the historic handshake in orbit, but the spirit of cooperation, laid down by the crews of Soyuz and Apollo, lives on. In April 2025, the Soyuz MS-27 spacecraftdeparted to the International Space Station with an international crew on board - Russian cosmonauts Alexei Zubritsky, Sergei Ryzhikov, and American NASA astronaut Johnny Kim. Joint work on the ISS today includes dozens of scientific experiments - from studying the effects of weightlessness on the human body to testing new materials. And if in 1975 cosmonauts and astronauts were just learning to work together, today it has become the norm - daily proof that space really unites. But it is important to remember: this norm became possible thanks to those who first extended a hand across the iron curtain of orbit. And new generations of researchers will have to not only continue this tradition, but also take it to a new level - to the Moon, Mars, and beyond.

Read more materials on the topic:

Will cope on its own: The Russian Orbital Station will be able to operate without a crew

Now on home

The device is powered by an AMD Ryzen AI MAX+ 395 processor with integrated AMD Radeon 8060S graphics

The use of ammunition increased the speed of combat operations of the "Msta-S" howitzers

The "KUB-10ME" Device Received an Optoelectronic Guidance System

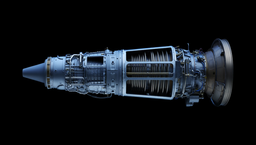

New turbojet engine will change the approach to supersonic flight without classic afterburner

Foreign delegation visited the "Parus electro" electrical equipment manufacturing plant

"The new system is more powerful than the existing version"

Sergey Marzhetsky stated that placing orders in the DPRK could become a realistic solution under sanctions

NDTV: India Aims to Acquire 40 Combat Aircraft

The autonomous platform can travel up to 60 km

Casting technology allows creating elements with geometry that cannot be obtained by other methods

The manufacturer promises compliance with global safety and quality standards

Remterminal to establish rolling stock production by 2032